Our ability to inhabit the space within a building’s loadbearing structure is a genuine modernization of architecture - a real change. Historically, this possibility was limited to attics within pitched roofs. All other structural components of a building such as walls and floors could contain installations, closets, nooks, niches, and alcoves; useful, yet only partially inhabitable spaces, at best. For example, we can look back at our previous tutor, where the structural space between domes in Wagner’s church can be accessed for maintenance and used to place equipment if necessary; but clearly, people aren’t supposed to stay there.

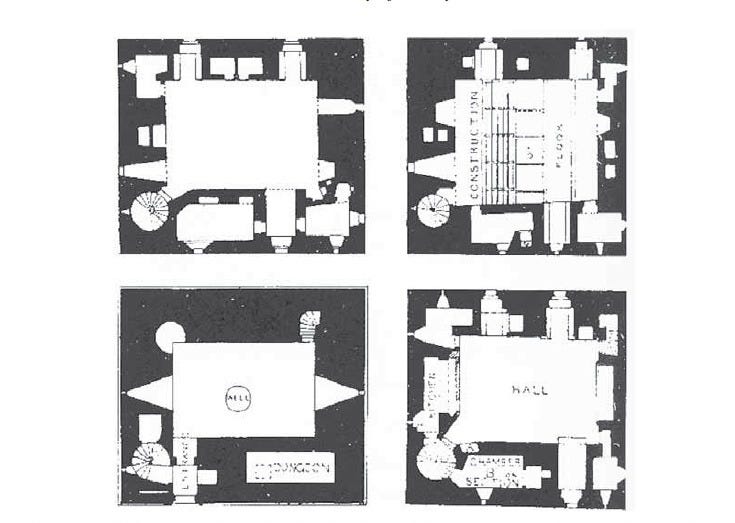

Among modern architects, it is Louis Kahn’s interest in medieval castles which has brought the question of inhabitable structures to the fore. In his case, said interest is an evident reference for his design of inhabitable structural elements, which he referred to as ‘hollow stones.’ In Kahn’s work the principle evolved into the division of served and servant spaces, understood as thickened floors and walls where installations and equipment can be easily accessed, while remaining independent from other, uninterrupted spaces meant for a building’s main uses.

Kahn’s sketches of British Castles. From Walls as Rooms: British Castles and Louis Kahn, where the original source is noted.

The discovery of building materials with a high resistance to both compression and tension, such as steel, reinforced concrete, and high-performance timber, made it possible to ensure a building’s stability with a fraction of the volume required by other materials, like stone, bricks, and natural wood. While some architects choose to use that ‘freed’ volume for buildings’ most prominent spaces, others consider that that there are notable benefits in using that available space within the walls and floors that surround those prominent spaces.

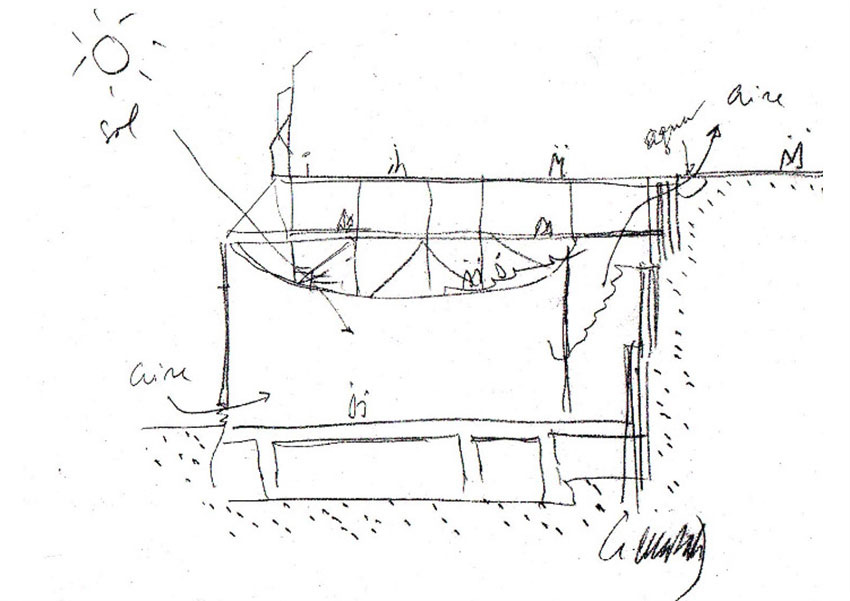

Our third tutor in this series is an excellent example of that second choice. The gym designed by Alejandro de la Sota for the Maravillas school in Madrid, faced a multitude of problems. The relatively small plot against a cliff left just one facade available for the intake of light and air - the rest of the building is literally sunken into the ground, like a huge basement.

The resulting box is divided vertically into four levels. At the bottom, within the foundations, is a swimming pool, illuminated by a slit of foot-level windows on the building’s facade. Above it comes the gym, illuminated by a strip of high windows towards the street, and covered by an inverted truss, inside of which de la Sota built classrooms - the third layer. Covering the volume is the roof, which became the school’s playground.

Cross-section sketch. From ‘The Maravillas School Gymnasium by Alejandro de la Sota: Embracing Modernity,’ where the original source is noted.

The way light is brought in through the single facade, and through reduced openings on the top slab and against the cliff, speaks of an enormous effort to literally illuminate the inside of the building’s structure - a most unusual concern. The vertical configuration of the classrooms - their shape in cross-section - suggests that rather than ‘following function,’ it is perfectly possible that an architect’s formal decisions follow a building’s physical performance.

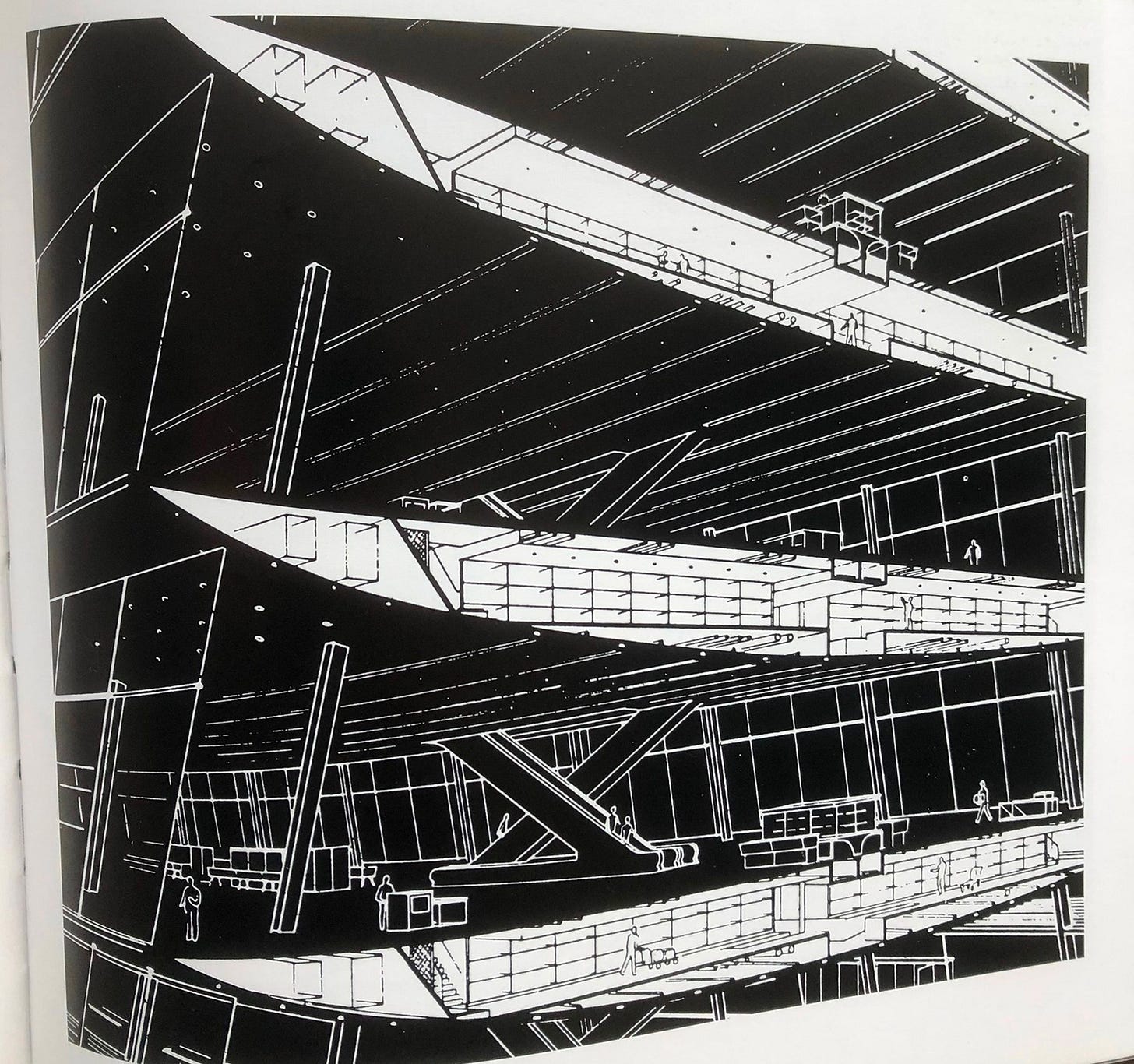

Inside a classroom. From ‘The Maravillas School Gymnasium by Alejandro de la Sota: Embracing Modernity,’ where the original source is noted.

Surely, de la Sota’s gym is not the only example of an inhabitable structure, but it is certainly one worth studying, given its extraordinary ability to combine technical ingenuity, aesthetic beauty, and creativity in the distribution of activities. Achieving a combination of classrooms, a playground, a gym, and a swimming pool in such a limited plot might certainly seem like a nightmare program for most architects. Here, instead, an extraordinary challenge was turned into an opportunity, which was beautifully solved by making the building’s structure (foundations as much as trusses) inhabitable.

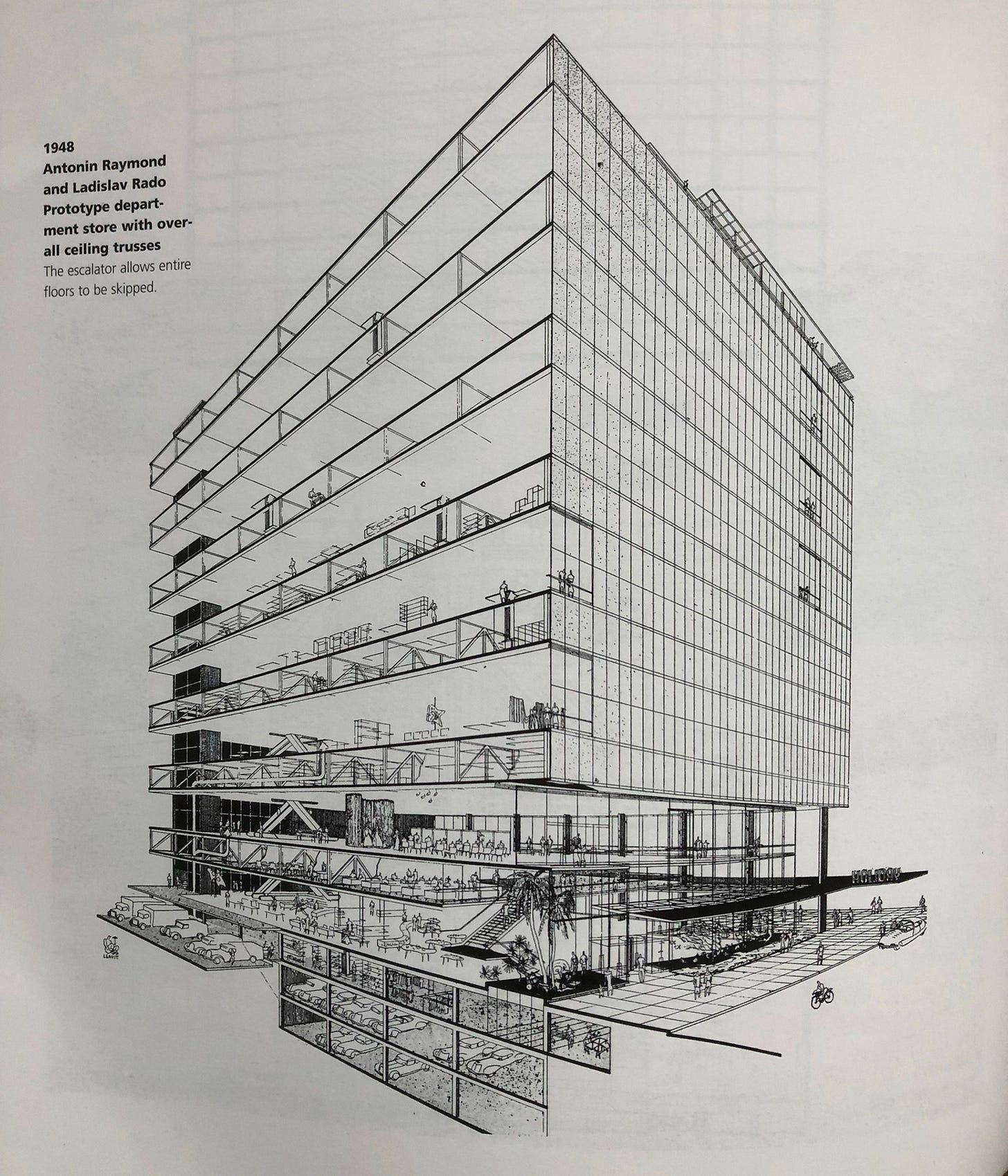

This principle is further illustrated in two drawings from the Rem Koolhaas-led GSD Project on the City’s Guide to Shopping. As we can see below, floors in commercial buildings are also made inhabitable, and escalators are extended to climb two levels at a time, making it possible to have all storage space (which tends to be enormous, in retail) hidden above and below shoppers who might probably never know that they seamlessly skip a floor every time they go up a level within a large department store, and that they are literally surrounded by a huge, invisible warehouse.

Two images from the GSD’s Guide to Shopping. Top image is from a 1948 project by Louis Parnes, bottom image includes original caption.

Enjoyed this one. The shift from “structure as barrier” to “structure as space” feels quietly radical. Do you think this kind of inhabitable structure has more potential in urban retrofits than in new builds?