architecture tutors: 2 - shell and inner lining

How many times have we heard Leon Battista Alberti’s argument that a building should be understood as a small city while a city should be seen as a large building? Come to think of it, we might just as well go further down in terms of size and claim that the clothes we wear are actually the first layer of building that separates us from the elements, while the buildings we use are just some sort of oversized apparel.

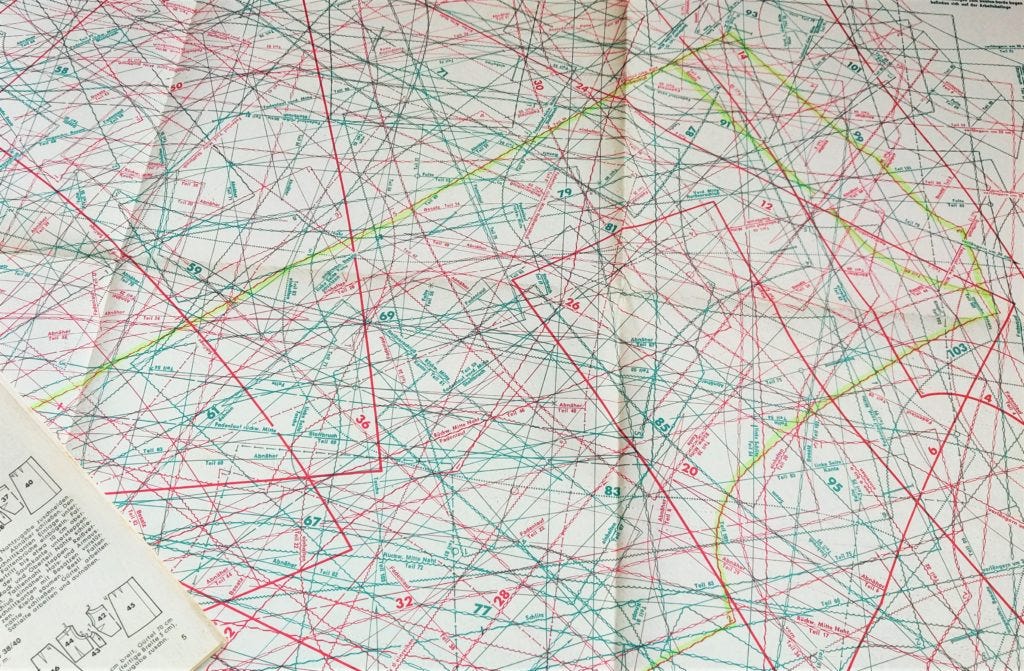

There are, no doubt, powerful and productive similarities between garment-making and architectural projection. So seen, sewing patterns are not very different from architectural projects expressed in technical drawings. In both cases, a three-dimensional reality - built space, the human body - is captured and communicated in the flatness of print. Furthermore, both representations express an envisioned end-result as much as they imply the instruments, processes, and methods required to achieve it.

sewing pattern from the German magazine Burda 7 (1969). Source: https://www.saturdaynightstitch.com/vintage-burda-patterns-how-to-trace/

Similarities between clothes and buildings don’t stop there, and allow us to recognize Otto Wagner’s project for the Church of Saint Leopold, in the Am Steinhof sanatory, as a valuable tutor. Among the many architects whose work elaborates on Gottfried Semper’s reflections on the textile origins of architecture (from F. Ll. Wright to Herzog & de Meuron) Wagner’s is certainly topical.

It is therefore no surprise that this relatively small building deals with two different - we could even say contradictory - requirements, just like a coat or jacket would. As we all know, said garments consist of two distinct parts. An outer shell of a rough and coarse material like wool faces the environment; while the inner lining, soft like silk or satin, enters in direct contact with our bodies.

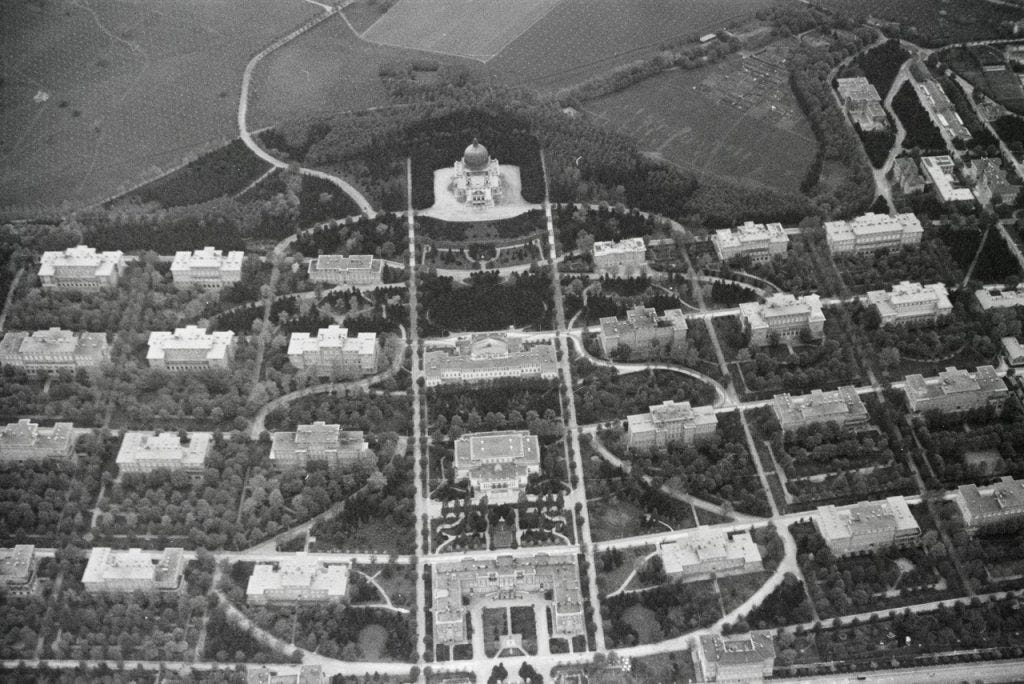

In this case, overlooking Vienna from the east, the church’s outer shell is made to be visible from afar.

the church atop the sloped sanatory compound. Source: https://www.publicbooks.org/modernism-heal-thyself/

The dome, visible from afar. Source: https://www.domusweb.it/it/speciali/guest-editor/norman-foster/2024/08/27/ospedali-del-futuro-architettura-della-salute.html

However, the height required to be seen is frankly disproportionate in relation to the building’s horizontal dimensions, and the interior space determined by those dimensions.

vertical vs. horizontal proportions of the church. Source: https://www.visitingvienna.com/footsteps/kirche-am-steinhof/

Interior. Source: https://www.wienmuseum.at/renting_otto_wagner_kirche_am_steinhof

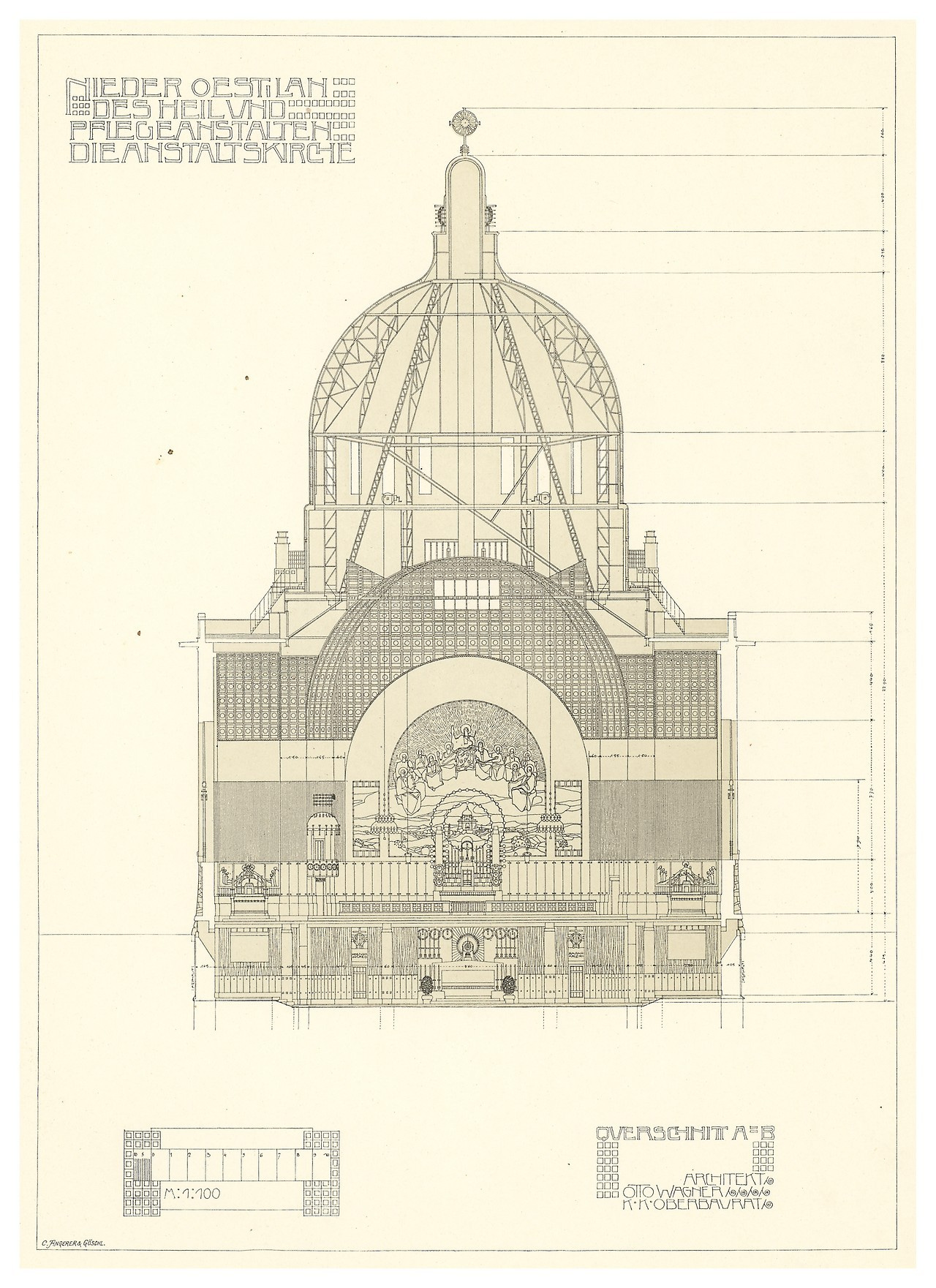

Faced with this challenge, Wagner acted like a skilled tailor and clearly characterized both layers of the project. Outside is a tall, textured, gilded dome, which unlike ancient domes does not perform under compression. It is, instead, a light shell, a mere cladding (i.e. clothing, same root), supported by a metallic structure from which the much lower ceiling is suspended. Different logics, different materials, different responses to different (in this case almost irreconcilable) requirements, are held together here by a beautiful structure that nonetheless remains concealed.

cross section. Source: https://hiddenarchitecture.tumblr.com/post/165412326815/kirche-am-steinhof-1904-otto-wagner

Like all good tutors, Wagner’s tailor-like approach to this church teaches us several useful lessons. For one, it shows us that it is possible to think about buildings as a superimposition of layers, which can - if useful or necessary - be non-coincident, differ greatly, or even contradict themselves. It also teaches us that there are alternatives to what some architects refer to as ‘honesty’ in both the formal and the technical resolution of buildings. While some buildings might benefit from showing what they’re made of and how they work, others might also benefit from hiding their nature and performance in order to show us other qualities instead. Finally, this beautiful example of early twentieth-century architecture teaches us that extremely important parts of our work (which will obviously demand enormous effort and creativity) might not be visible to others, and should still be done with great intelligence and care.