circular

A recent social media post chronicles a professional study trip. Last June a group of first-year architecture students from Buenaventura, Colombia’s main port on the Pacific coast, travelled to Cali, the provincial capital. Their visit to the local chapter of the architects’ association coincided with an exhibition of the country’s 29th Biennial of Architecture and Urbanism, which took place last year.

Despite its key role in the Colombian economy, most of Buenaventura’s inhabitants live below the national per-capita U$ 6,819 per year. Their architecture program is offered by a public university established in 1988.

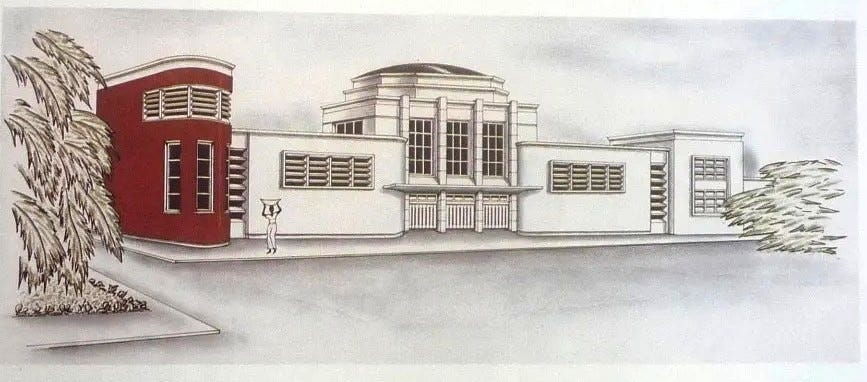

While the local (long decommissioned) train station built in 1933 by the Italian architect Vicente Nasi is part of the nation’s heritage, besides a handful of modernist buildings the city is not often recognized for its planning or design.

The Instagram post makes clear that visiting Cali offered this particular group of students the opportunity to learn about their profession by experiencing buildings and urban areas different from their own, but also by seeing a selection of the best architecture produced in the whole country in the past two years.

I studied architecture in Cali. Between its foundation in 1536 and 1910, when it became the capital of a newly created province, Cali was a town of less than 30,000 inhabitants; which literally exploded from the 1920s onwards, after road and train connections were established with the coffee regions in the north, and west with Buenaventura. The industrialization process made possible by these connections still supports the current two-million-plus inhabitants, whose per-capita GDP climbs up to U$15,900.

Cali’s first architecture school was established in 1947, with a radically modernist direction. The city’s rather marginal role in the colonial and first republican economies explains the amount and quality of architectural heritage in the foundational center, which is complemented with a few neo-classical and several really beautiful modernist buildings. While parts of the city have evolved without much planning or design, as students of architecture we could articulate what we saw and read in books and magazines with our study of exemplary local buildings and neighborhoods. In addition our teachers took us on study trips to the nation’s capital, Bogotá.

Compared to México or Lima, which were founded on imperial cultures themselves, Bogotá did not play a cardinal role within the Spanish empire. It has nonetheless been a national capital since its foundation in 1538, which reflects in the value of some of its buildings and public spaces. Large and carefully built houses, churches, and monasteries from the colonial period are interwoven with neoclassical government buildings, modernist high-rises and contemporary office towers. Bogotá is home to the nation’s first faculty of architecture (since 1929 as a program within civil engineering and after 1936 as a faculty in its own right). There’s a consolidated professional culture in the city, supported by a per-capita GDP that rises to U$ 21,800.

In Bogotá students of architecture have a considerable amount of buildings and urban areas to learn from, ranging form large infrastructure projects to individual homes, and from public spaces to qualitative low-cost housing. Besides modern and contemporary works by the country’s most distinguished professionals, competent foreign architects and firms have been consistently present in the city’s construction. There’s also an architecture museum in Bogotá. Specialized exhibitions and academic events take place there as well as in other venues on a regular basis. Architecture magazines, scholarly journals, and books are published and read by professionals and students from the city’s ten accredited faculties; who also go on study trips, in many cases abroad.

Spain is a popular choice, not only for the language, but also for its extraordinary architectural culture. A city like Barcelona, for instance, is home to some of the most beloved architectural publishers in the Spanish speaking world. Founded in 1875, the world-class ETSAB is now complemented with a handful of cutting-edge institutes, and supported by a robust institutional framework of museums, galleries, and other professional fora. Remnants from Roman, Romanesque, and Gothic architectures intertwine with the uniqueness of Catalonian Modernism, celebrated city planning, and more recently, world-class contemporary design. One could spend a lifetime just studying the architecture of Barcelona and its surroundings, developed over millennia, and currently supported by an average per-capita GDP that comes close to U$40,000 per year.

Architects formed in Barcelona (we could also think of Seoul, Buenos Aires, or Sydney) also go on study trips, in many cases to cities with robust economies like London or the ‘Bos-Wash’ conurbation (with per-capita GDPs of $93,591 and $104,106 respectively), in many cases to cities with high standards of livability; probably not anymore to experience buildings and urban areas that are too different from the ones they inhabit, but rather to be confronted with professional cultures that have developed valuable forms of knowledge, based on high levels of organization and professional discipline.

It goes without saying that architects who enjoy those high standards of livability and professional cultures also go on study trips, as we learn from a recent social media post. Between July and August, for instance, architecture students from the University of Cambridge (founded in 1209, with architecture established as a department in 1912) will travel to Cali to work on the city’s peripheries. In the meantime a considerable number of architectural excursions and workshops are planned to some of the many cities around the world whose circumstances and indicators resemble those of Buenaventura, Colombia’s main port on the Pacific coast.

Vicente Nasi, Buenaventura Train Station (1930 - 1933), from his book Continuidad / Continuity (1987).