building association

In the different texts included in his collected Writings on Architecture, Kentucky born architect Paul Rudolph insists on a few claims regarding professional education and practice. Formed as an architect in the second postwar, his work could not avoid dealing with the notable advantages, but also with the evident disadvantages of modernism. In this sense, Rudolph offers valuable complement to the work of contemporary European colleagues - think of Giancarlo de Carlo, or Aldo van Eyck - who also faced similar dilemmas.

Among the intriguing ideas developed by Rudolph in the articles, interviews, and speeches collected in this small volume, is the realization that some of the most admired manmade environments in the world were built with remarkably few materials. Diversity, from Rudolph’s perspective, is neither always nor automatically a good thing; and to prove it he notes how the abundance of building materials and technical alternatives available to us has not necessarily led to an evident improvement in the quality of buildings and cities. In his words:

‘One problem is that we have almost too many materials. The best architect always uses the fewest materials. That goes for towns too. The Mediterranean hill towns are built entirely of one material, and they’re marvelous. Beacon Hill in Boston is built all out of bricks, and it remains one of the most humane places. Each person didn’t build with a different material, they used the same material in most imaginative ways, so that the whole is always more important than the individual parts.’ (p. 101 - 102)

As we see, Rudolph was keen on analyzing excellent architectures from the past, in order to reveal the reasons that explain their beauty and admirable performance; but he was also optimistic about progress. Underlying both attitudes are two defining formative experiences. Besides formal training, first at Auburn University and then at Harvard, Rudolph mentions:

‘Four years in the U.S. Naval Reserve at the New York Naval Shipyard provided the opportunity of observing heavy construction techniques in terms of ship building… I began to understand the necessity of seeing a design from the workman’s point of view and, in terms of the sequences of the various trades between hull and compartmentalization of a ship and the clarity of each part...’ (p. 9)

And adds,

‘I was fortunate to receive a fellowship to travel in Europe. One can talk of architectural space, but there is no substitute for actually experiencing a building or a city, of seeing architectural space at various times of the day and under all types of weather, and for seeing forms in use. With notable exceptions I was impressed much more by the great architecture of the past than by the contemporary efforts.’ (p. 9 - 10)

From the resulting, syncretic approach to buildings and cities, two topics are singled out as key concerns for postwar architects. The first is scale. According to Rudolph, the scale of buildings and cities remained relatively stable throughout millennia, only to be suddenly transformed by the appearance of the car and its effects on our perception of time and distance. The second main concern is space, which in Rudolph’s opinion has never been really understood by architects, but is rather taken as a given, and therefore remains insufficiently examined. Together, both concerns converge in a pragmatic appraisal of modernism.

According to Rudolph, distinct cultural transformations (such as new technologies, urbanization, population increase, scientific discoveries, and so on) made modernism inevitable; and - writing in the 1970s - explain why some features of modernist architecture remain in vogue. On the other hand, according to Rudolph,

‘one of the most serious charges against Modern architecture is its failure to produce understandable theories about the relationship of one building to another.’ (p. 21)

Focus on relationships between buildings, but also between buildings and their context, allows Rudolph to make a distinction between modernist architecture, and a lesser variant thereof which he refers to as ‘international modernism.’ The first corresponds to the work of extraordinary architects; not only able to adapt built form to unprecedented uses and their concomitant logics, but equally capable of solving timeless architectural questions competently.

These timeless questions mostly regard the ways in which a building relates to other buildings as well as to its own surroundings. Rudolph asks, for instance, how does a building touch the sky? To be sure, this can happen in very different ways, all of which can be evaluated - some will work better than others. A sunset, a clear blue sky, dark clouds before a storm - these and other ‘skies’ are definitely not the same when seen against a flat roof, the jagged profile of a series of pitched roofs, a sharp steeple, or a dome. And then, how does a building turn a corner, how does it touch the ground, how does it extend an invitation for you to enter? Such questions require that thought goes beyond the building itself, and incorporates the context that building is part of.

Again, while excellent modernist architects clearly came up with well crafted answers to these questions, truth is that the watered down version of modernist theory that became mainstream in many parts of the world hardly considered these questions. Numerous architects appeared to be content with doing half the job, so to speak, by accommodating activities sufficiently well and by offering unrivalled levels of efficiency, both constructive and functional, within the building, not beyond it.

Those two achievements (functionality + state of the art building technology) - Rudolph claims - are no doubt commendable, and should therefore not be ‘thrown out with the bathwater.’ But equally important architectural tasks (such as those required to link architecture with its context or to associate different buildings to each other) remain neglected in many cases, and the results are there for us to see.

Fortunately it doesn’t seem too difficult to correct course, solutions are known and readily available, architecture is not ‘rocket science.’

‘The ways in which a building relates itself to the ground are actually very few, no more than five or six, and they are so frequently mixed up with one another in Modern architecture that there is a certain lack of consistency.’ (p. 43)

Improving on the way architecture establishes rich associations requires a better understanding of scale, one that is relevant to the present; as well as further development of what we know about architectural space, also in relation to current culture. As important as the relationships that can be established between buildings and their surroundings, it is crucial that we conceive and construct buildings that are capable of establishing positive associations with each other.

Of particular interest in this regard is Rudolph’s mention of different kinds of buildings, observed in some of the most beloved cities in the world. Rather than describing their size, use, or style, in his opinion every comprehensible built environment should include buildings that perform in the following ways:

‘(1) a focal and centralized building, (2) a focal building, which is attached to another, (3) flanking buildings, (4) crescent buildings, (5) row buildings, which form a wall, (6) building at ‘knuckle’ or bend in a row of buildings, (7) concavely curving building, (8) building which turns a corner, (9) building which terminates a row of other buildings, (10) building which acts as a gateway, (11) building which marks a entrance, (12) transitional building, leading from one to another, (13) building which acts as a base for others, (14) building which is placed on top of another, (15) building which forms a courtyard, (16) building which forms a bowl of space, (17) convexly curving building forming a space, (18) building which deflects circulation, (19) building which forms a bridge, (20) building recessed in a wall, (21) building which forms a terrace, (22) stepped, terraced buildings, (23) building which forms a loggia, (24) cellular buildings which multiply, (25) building which acts as a pivot in space, (26) building which partially shields others, (27) building which acts as a hill, (28) cloister-type building which forms a precinct for others, (29) building acting as a generator for others, and (30)tall buildings can be divided into points, slabs, bent slabs, intersecting slabs, sentinels, stepped in one or several directions, variations on the pyramid, and irregular topographical buildings.’ (p. 110 - 111)

Returning to the notion of diversity, a paradox becomes evident. International modernist architects embraced technological development by increasing the amount of construction materials and techniques. In exchange, they appeared to radically reduce the number of built forms and their corresponding performances (in the terms listed above). Entire neighborhoods were made with very few kinds of buildings, incessantly repeated. Absent buildings with articulating or associative roles, such as ‘knuckles,’ transitions, gateways, and pivots, spatial quality was substantially eroded.

Three clear lessons come forth from this short review of Rudolph’s Writings on Architecture. The first is the recognition that, essential to an architect’s work, are the knowledge and skills required to associate things. Materials relate to each other into building elements; which in turn connect to become spaces; which cluster into building parts that add up into forms (classifiable as types), streets, blocks, and neighborhoods, all the way up into cities. At each level of association, materials, elements, spaces, parts, and wholes, relate to each other as much as they relate to what surrounds them.

The second thing we can learn from reading Rudolph is that rather than diversifying only some aspects of our work, such as the amount of materials and building techniques employed in construction, we can preserve and improve the quality of our buildings and cities by recognizing diversity at different levels. Continuing with performance, we can efficiently host a particular use or activity and at the same time recognize the importance of aesthetic, urban, or environmental performance. Such concerns needn’t be mutually exclusive.

By focusing on a narrow interpretation of a building’s performance (‘dwelling’ or ‘office’) while ignoring other, equally important aspects of that performance (‘turning a corner,’ or ‘pivoting’), modernist architects thought they were being efficient; they probably felt that they were creating state of the art machines - great on their own, but actually incompatible with each other.

We can still single out a third and final lesson. Albeit tacitly, Rudolph suggests that we should consider the buildings we create as mirrors, rather than as magnets (our terms, not his). This might require some explanation. While magnets concentrate and attract, like we do when we justify our design decisions ‘inwards’ (as in: ‘all neighboring buildings are two stories tall, therefore mine will also be two stories tall’); adopting a ‘mirror’ attitude allows us to consider how each of our decisions can establish a fruitful relation ‘outwards,’ with things that are certainly beyond our control. What if, for instance, besides being excellent in and of themselves, our projects deliberately start aiming to bring out the best in other architectures? Like good wine, capable of enhancing the food it is paired to, what if our work could actually highlight, reveal, or even increase the beauty of what surrounds it?

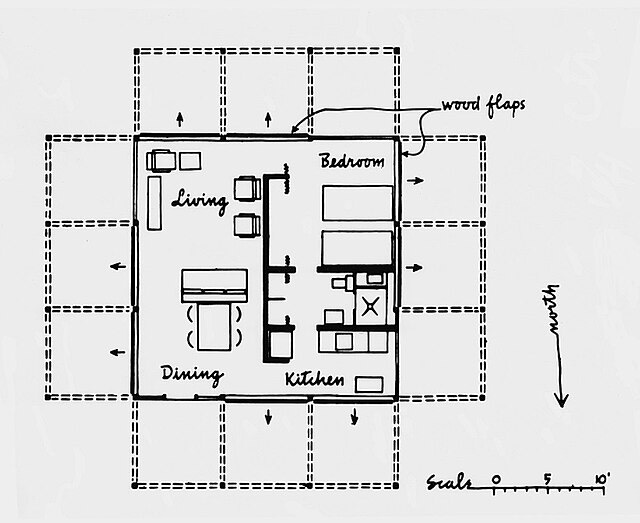

Paul Rudolph, Walker Guest House (1952), source: Wikimedia Commons